‘Staying Amazing!’ Striking NYP Nurses Press the Fight for Safe Staffing

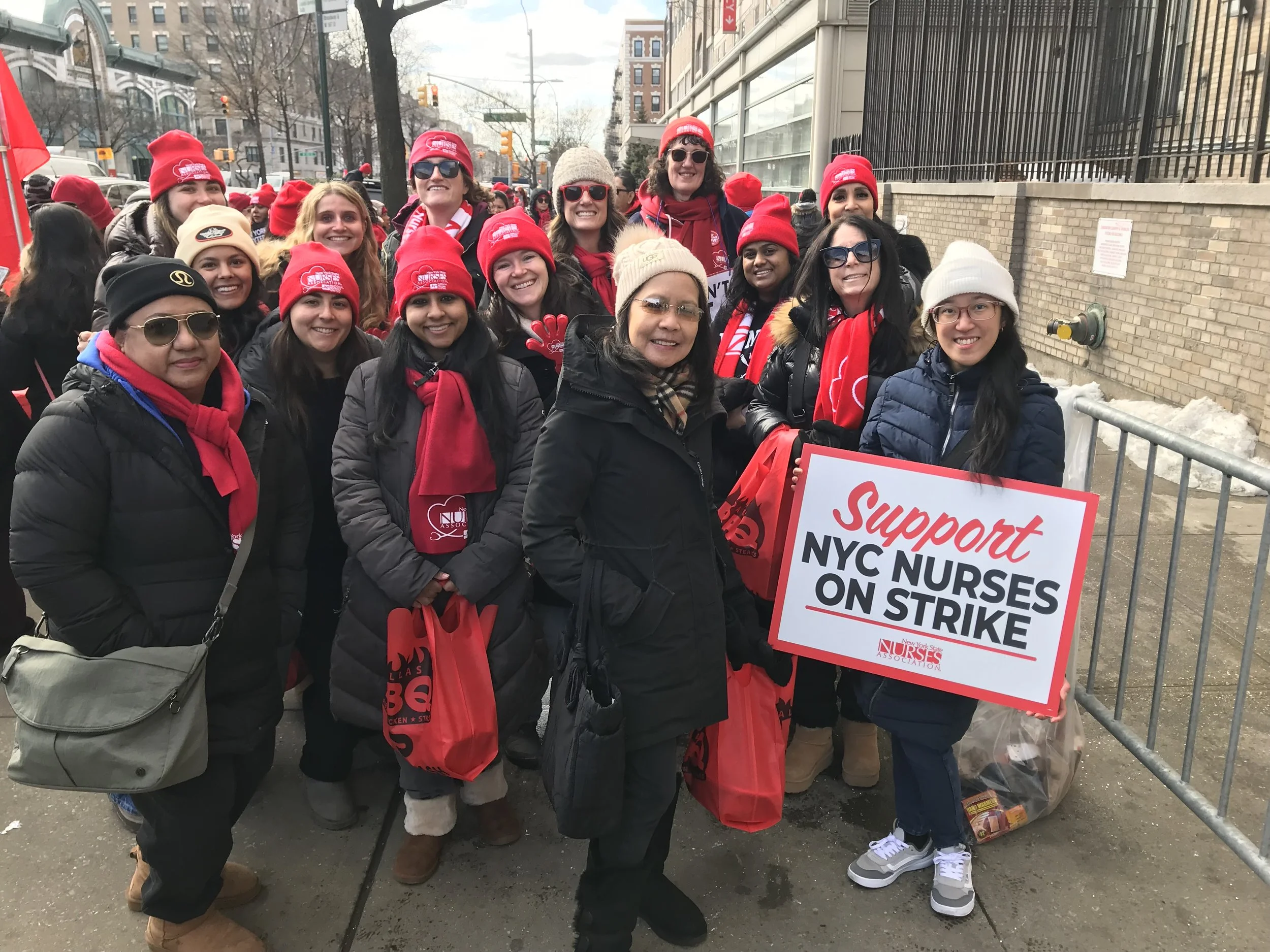

“We’re still fighting for safe staffing, which is why we were out here in the first place.”— Marielle Medina, cardiac and electrophysiology nurse. Above: Striking NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital nurses on the picket line this week. Photos/Steve Wishnia

By Steve Wishnia

One day after they rejected a proposed new contract by a 3–1 margin, nurses at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital were back on the picket line on both sides of the Washington Heights medical center Feb. 12.

“We’re still fighting for safe staffing, which is why we were out here in the first place,” Marielle Medina, an 11-year cardiac and electrophysiology nurse, told Work-Bites on the Fort Washington Avenue side, trying to be heard amid the sonic gumbo of strike chants, fire sirens, dancehall reggae, car horns—some in solidarity, some in annoyance at the traffic—and a percussive array of drums, plaster buckets, red bells and hand-shaped clickers, and Korean kkwaenggwari hand gongs.

The NewYork-Presbyterian nurses rejected the proposed three-year agreement by a 3,099–867 vote. New York State Nurses Association members at Montefiore, Mount Sinai HospitalandMount Sinai Morningside and West had overwhelmingly ratified a similar deal Feb. 11.

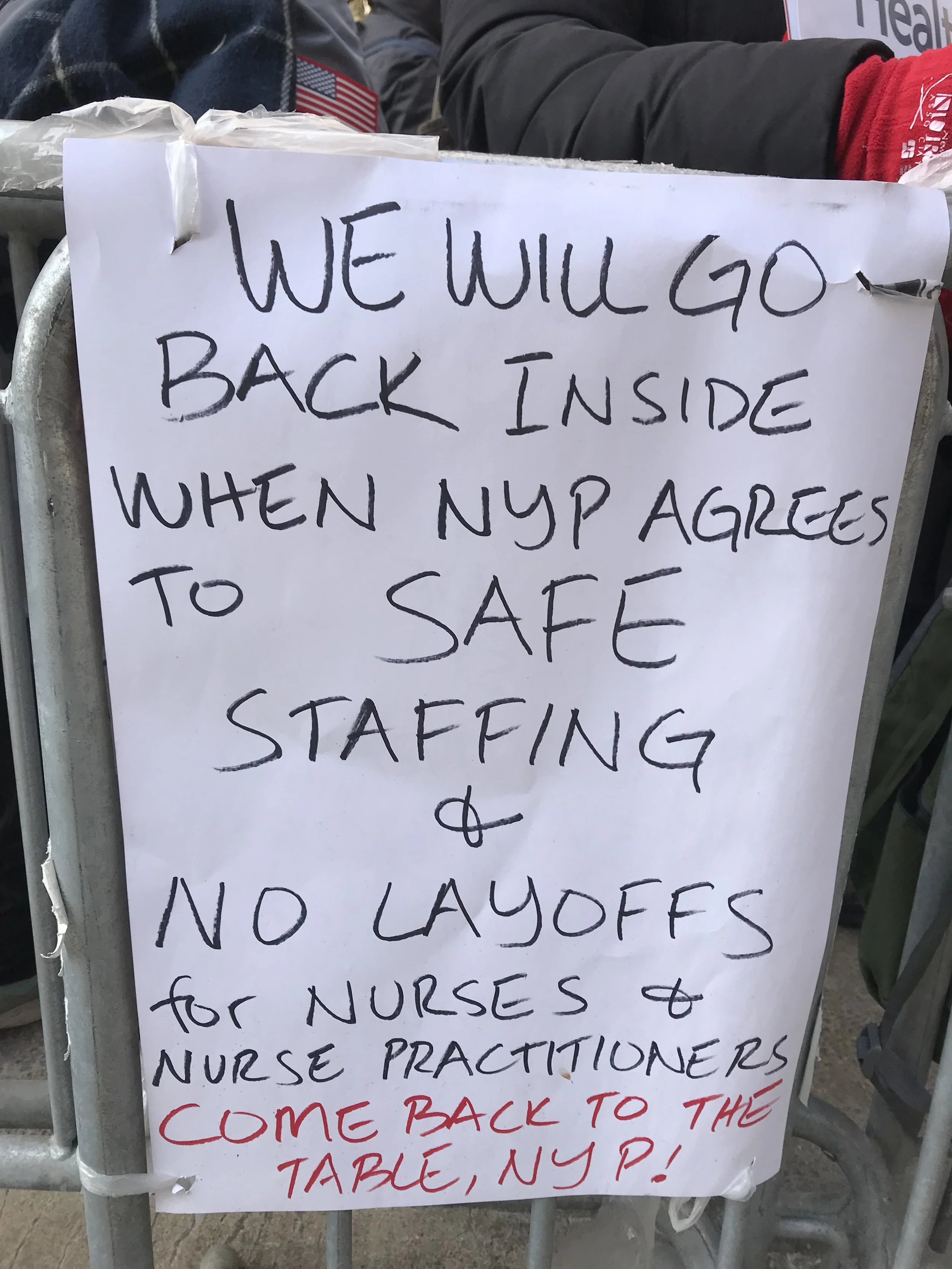

Nurses on the picket line said they were fine with the proposed deal’s 4% annual raises and its preserving their health-care and pension benefits. But they objected that the version for NewYork-Presbyterian did not contain enforceable staffing minimums, unlike those at the other hospitals; it did not include language protecting them against further layoffs; and the 65 nurses it pledged to hire was far less than what was needed to relieve staffing shortages.

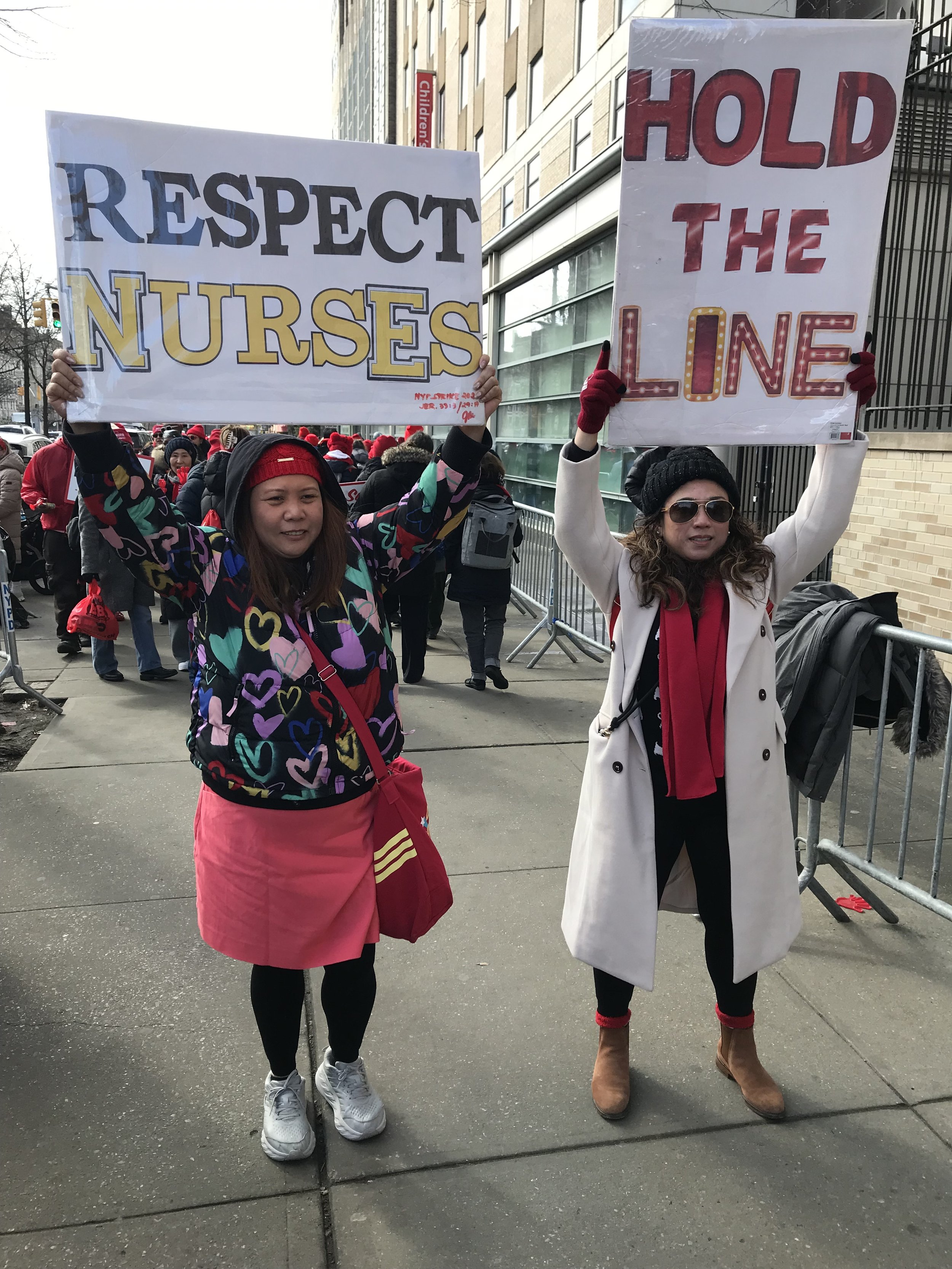

“The fight is not wages. It is safe staffing,” said L.S., a nurse picketing in front of NewYork-Presbyterian’s Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital on Broadway, amid a larger but quieter crowd. She did not want to give her name for fear of retaliation.

The NewYork-Presbyterian nurses had reached a tentative agreement for the same pay increases and benefits as the other hospitals, said M.G., another nurse on the Broadway side.

The 65 full-time-equivalent nurses NewYork-Presbyterian agreed to hire in the rejected contract “looks like a lot to the naked eye, but it’s not when you dig down,” a NYSNA staffer who asked to be anonymous told Work-Bites. To provide 168 hours a week of coverage, they explained, it would add an average of 12 nurses per shift—and that would be divided among four campuses.

A NYSNA spokesperson said it had sought 100 new nurses.

The nurses said that they also needed protections against layoffs. NewYork-Presbyterian was the only one of the three hospital chains to lay off staff last year, they said, when it axed 1,000 workers, including 46 nurses and nurse-practitioners—with only a few days’ notice, said L.S.

They are demanding language “to ensure we’re not replaced by nonunion nurses,” she continued. Management, she added, is “union-busting. That is their goal.”

“If we go back without that language, we will be replaced,” said L.V., a nurse-practitioner. Nurse-practitioners are vulnerable, she explained, because they perform similar functions as physician assistants, who are not unionized. The 15 nurse-practitioners laid off last May were replaced with trainee doctors, bargaining-committee member Sophie Boland told Work-Bites when the strike began Jan. 12.

The NewYork-Presbyterian contract offer also did not include the enforceable staffing minimums contained in the Montefiore and Mount Sinai agreements, both M.G. and Medina told Work-Bites.

There was “nothing that holds them accountable, as other hospitals have proven they can,” M.G. said. “If they want to make the three of us across-the-board, they can add that language.”

“That and job security are the two big pieces,” Medina said.

NYSNA leadership had urged NewYork-Presbyterian nurses to ratify the contract, which Medina said was “not the right thing for them to do.”

“We elect nurses and nurse-practitioners to speak for us because they work on the same floors as us and understand our struggles,” she told Work-Bites.

Management recalcitrant

The walkout was an unfair-labor-practice strike because management was not bargaining in good faith, Medina said.

“NewYork-Presbyterian has not been coming to the table,” she said. “They’ll be in the building, but they’ll only be at the table for 20 minutes.”

Montefiore and Mount Sinai nurses “were able to negotiate with management,” said M.G. “Our management here did not bargain in good faith. They only showed up a few times.”

That’s a pattern that goes back to when talks started last August and continued even after NYSNA issued its 10-day strike notice, Boland told Work-Bites in January.

“We are disappointed that our nurses did not ratify the mediators’ proposal,” a NewYork-Presbyterian spokesperson said in a statement. “We believe the proposal, which includes compromises, is fair and reasonable and reflects our respect for our nurses and the critical role that they play.”

The statement did not mention staffing or job-security issues—or indicate that management would negotiate on them unless pushed.

“For now, we remain willing to honor this current proposal for reconsideration,” it continued. “It's critical to remember that the economic terms we agree to will directly affect New York City’s safety-net hospitals.

“Next steps are still being determined. In parallel, we are inviting our nurses to return to work if they choose.”

“We have reached out to NewYork-Presbyterian to schedule bargaining dates ASAP, and we have yet to hear back from them,” a NYSNA spokesperson told Work-Bites.

“I would like NewYork-Presbyterian to come back to the table,” Medina said. “We’re ready when they are.”