Inside the ‘Grotesque Legal Fiction’ Enslaving Home-Care Workers

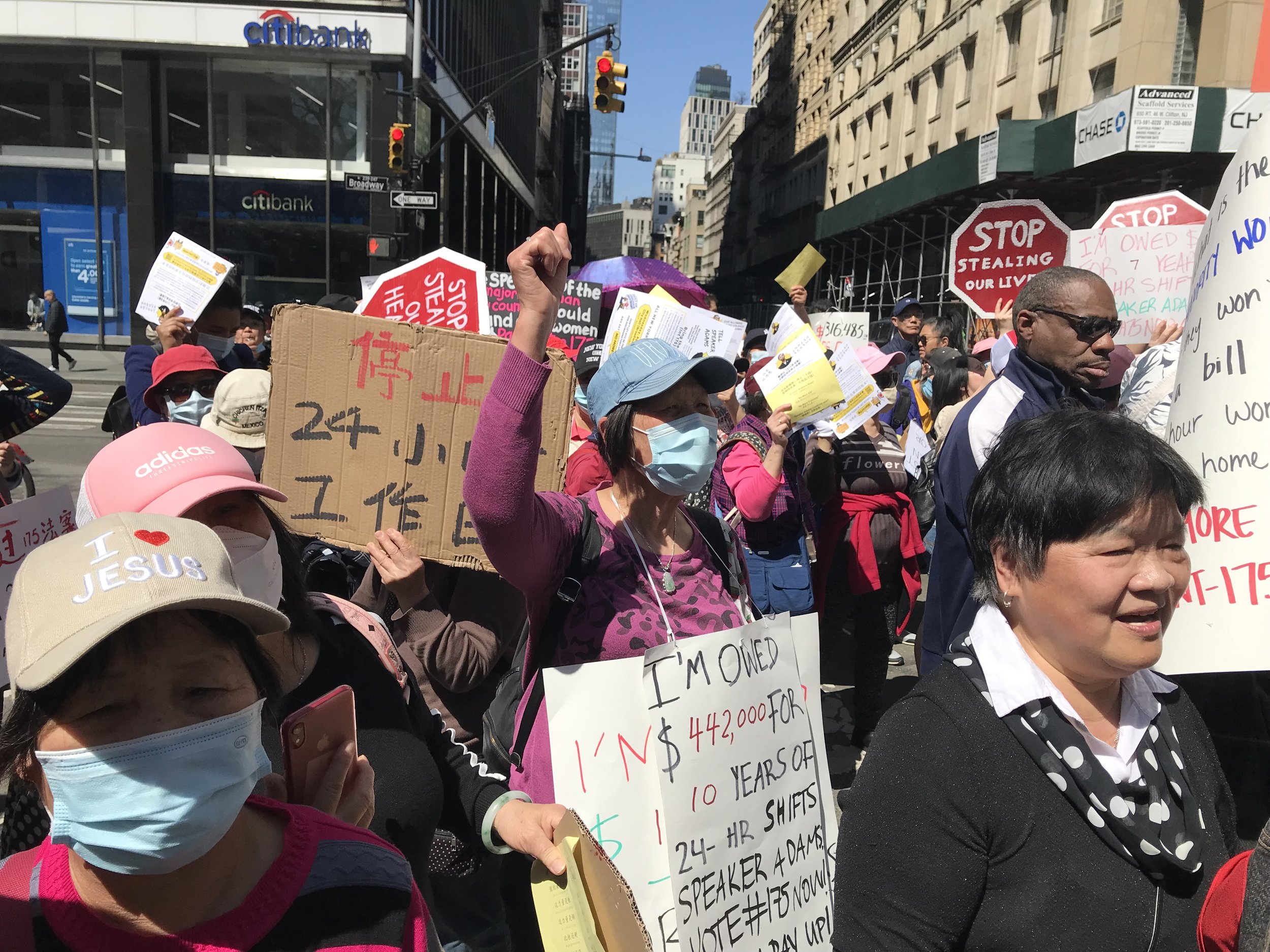

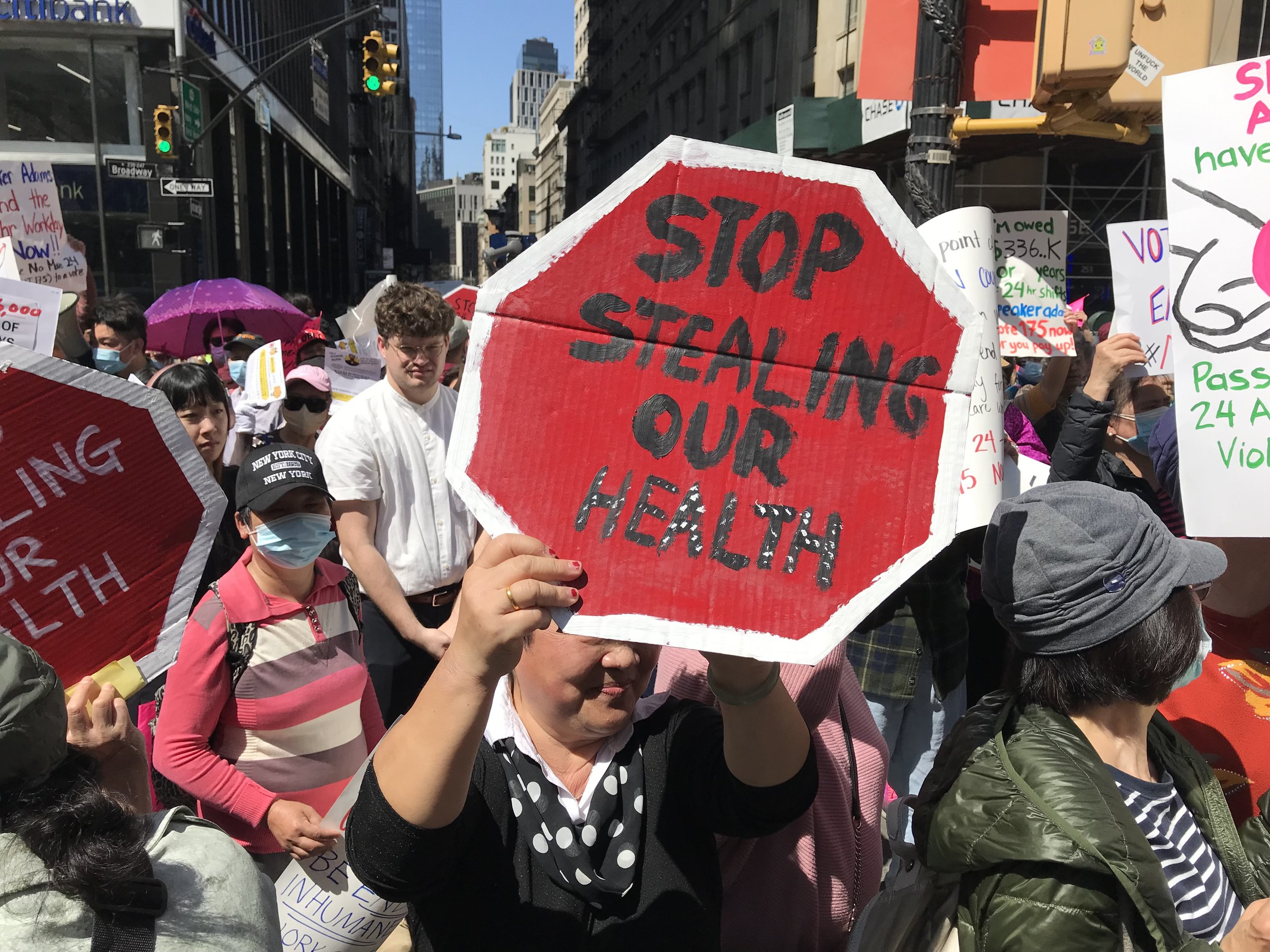

Home-Care workers rallied outside City Hall earlier this month to demand the New York City Council finally do something to help end legalized wage theft in the industry. Photo by Steve Wishnia

By Steve Wishnia

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated since its original publication to include further information about the budget and more from Assemblyman Harvey Epstein’s office.

In 1960, when the federal minimum wage was $1 an hour and did not cover workers in nursing homes or construction, the New York State Department of Labor established a regulation that home health-care attendants working 24-hour shifts should only get paid for 13 hours, because they have the other 11 hours off for eating, sleeping, and breaks.

That regulation defined home health-care workers as the equivalent of domestic servants, former Assembly Health Committee chair Richard Gottfried told this reporter last year. The rule might make sense for live-in kitchen staff who are on duty for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, but get breaks in between and can sleep nights. For home-care workers, it’s a grotesque legal fiction that authorizes wage theft.

“I couldn’t sleep for even one hour,” attendant Nu Jun Zhu, speaking in Chinese through a translator, told a rally outside City Hall Apr. 12 demanding that the City Council pass a bill to limit shifts to 12 hours. “My patients had to be lifted from a wheelchair to the toilet 20 times a day.”

The Council bill to end the “24 hours work for 13 hours pay” system, Intro 175-A, has been stalled, however. Eight of its 25 cosponsors withdrew earlier this month, and Speaker Adrienne Adams opposed it. “New Yorkers with disabilities, among other important stakeholders in our city, have raised significant concerns about this bill that need to be resolved,” a Council spokesperson said in a statement to the media after the Apr. 12 protest. The speaker, they added, has “no interest in pitting groups against one another.”

Intro 175-A has lost eight co-sponsors in the City Council this month.

“24-hour shifts are an exploitive practice and workers should be paid for every hour they are expected to remain in a client’s home,” 1199SEIU spokesperson Bryn Lloyd-Bollard said in a message to Work-Bites. But the union, which represents a substantial share of the estimated 130,000 home health attendants, has “concerns about the current language” of Intro 175-A.

He said that without the state funding “necessary to convert the 24-hour shifts into split shifts,” it risks pushing thousands of home-care clients into nursing homes and costing caregivers their jobs.

Disability-rights groups and nonprofit agencies that hire home caregivers have expressed similar sentiments.

Councilmember Christopher Marte (D-Manhattan), Intro 175-A’s lead sponsor, told Work-Bites at the Apr. 12 rally that he was frustrated that the bill’s supporters had worked with the unions and disability-rights groups to amend it, but “still, we haven’t gotten anywhere.”

For example, the bill was amended to raise the limit on home health attendants’ workweek from 50 to 56 hours. District Council 37 Local 389 President Margaret Glover, whose union represents almost 7,000 attendants, testified at a Council hearing last September that the 50-hour maximum would prevent workers who need the extra money from working overtime.

Home-care workers hold a vigil outside City Hall on April 13 in support of Intro. 175-A. Photo by Joe Maniscalco

Local 389 and DC 37 did not respond to messages from Work-Bites, but 1199SEIU still has problems with the limit. The bill says “no employer” shall assign a worker more than 56 hours a week, so, Lloyd-Bollard said, people who worked for different agencies could work more than that without getting overtime pay.

As home-care agencies are primarily paid through reimbursements from Medicaid, the money to pay workers for all the hours they put in would have to come from the state. State Senator Roxanne Persaud (D-Brooklyn) and Assemblymember Harvey Epstein (D-Manhattan) introduced bills to end 24-hour shifts in the 2019-20 and 2021-22 sessions, but neither got as far as a committee hearing.

Epstein’s office said he plans to introduce a similar measure this year once it gets a bill number, with the goal of including its language and an adequate appropriation in the budget. A spokesperson for Persaud said she “is still very engaged on this matter and plans to reintroduce the legislation once some issues are worked through.”

1199SEIU estimates that 5 to 7% of the home health attendants it represents do 24-hour shifts. Its priority is a bill to raise the state’s minimum wage to $21.25 an hour over the next four years, and preserving a provision in the 2022 and 2023 state budgets that raised attendants’ pay to $3 above the state minimum. Gov. Kathy Hochul’s proposed budget would eliminate that $3 premium.

Meanwhile, the state Court of Appeals’ 2019 decision that upheld the state’s 13-hour regulation did say that workers could claim full pay for 24-hour shifts if they could document that they hadn’t gotten at least five uninterrupted hours to sleep. So far more than 550 have filed such claims with the state Labor Department, with some seeking more than $300,000 in back pay and damages. That process has just begun, however, and several steps remain — from mediation with employers to possible court challenges — before workers will be able to collect anything.

That leaves the issue of 24-hour shifts in the same place it was when Intro 175 was introduced last year: Widespread support for its basic principles, but powerful opposition to putting them into practice.

Councilmember Marte and the Ain’t I A Woman campaign, which has been organizing to abolish 24-hour shifts for more than seven years, say it’s not a question of funding, but a question of justice: Workers deserve to get paid for every hour they put in.

On the other hand, the money has to come from somewhere. If it comes from the state budget, estimates of the cost range from about $650 million to $1.2 billion a year. If nothing is changed, it will continue to come off the strained backs of the women who provide the care.

“It’s like we work the night as a gift to them,” Trinidad Castro, a 47-year-old mother of six children who works 24-hour shifts caring for an 85-year-old woman, told Work-Bites after the Apr. 12 rally.