Phil Cohen War Stories: Montagnard Insurgents Join the Union

War Stories By Phil Cohen

Editor’s Note: This is Part I of Phil’s two-part story about a community of Montagnard tribesmen who fought alongside US Special Forces in the Vietnam War, were abandoned for 20 years, and ultimately allowed to immigrate to Greensboro, North Carolina many years later. That’s where Phil met them working at a Kmart warehouse and started organizing.

Montagnards were an ethnic minority of ancient warrior-tribes living in the central highlands of Vietnam, who considered themselves a separate nation with their own languages and religion. Having suffered a long history of persecution by the Vietnamese, they were recruited during the 1960s by American Special Forces to engage a common enemy. The Montagnards’ warlike upbringing and intimate knowledge of local terrain made them invaluable assets and the military guaranteed their protection regardless of the war’s outcome. They were dramatized in a somewhat exaggerated fashion by the movie Apocalypse Now.

During the fall of Saigon in 1973, as Americans scrambled for safety, the Montagnards were abandoned to fend for themselves against genocidal retaliation by Vietnamese forces. The betrayed warriors continued fighting in the jungle for another twenty years, living off rats and monkeys while defending their villages.

But these stoic tribesmen hadn’t been entirely forgotten. Green Beret Sergeant George Clark formed an organization and mounted a compelling media campaign, ultimately embarrassing the military and Congress into arranging their transport to the United States, beginning in 1986. The majority ended up in Greensboro, North Carolina.

American union busting escalated during the 1990’s. Union avoidance consultants encouraged industrial employers to create in essence a Tower of Babel by flooding their workforce with newly arrived immigrants from various cultures who spoke little English, and would therefore be difficult to organize.

Kmart opened a Greensboro warehouse in 1992 and realizing they were in the midst of a militant ACTWU stronghold, management embraced this strategy, hiring numerous employees from Africa, Mexico, and Southeast Asia. Dozens of Montagnard refugees ended up on their payroll, many securing preferred positions as forklift drivers, transporting merchandise from shipping docks to storage modules, which was far less of a grind than loading or unloading trucks. Though unable to understand verbal or written instructions, having spent years navigating through jungles, learning their way around a warehouse presented little challenge.

Following a bitter three-year campaign, Kmart signed a generous collective bargaining agreement in 1996 and the next year I was assigned as an internal organizer and representative. I’d already developed a well-honed strategy for communicating with immigrant workers through the assistance of Kathleen Quinby, president of Language Resources. She not only helped new arrivals find housing and work in Greensboro, but also identified bilingual individuals within each group to employ in her translation service.

I distributed monthly leaflets in seven languages, updating workers about recent victories and grievances the union was still fighting for. Each dialect was on different colored paper for easy identification. Most of the foreign employees were deeply touched by the gesture after being ignored by organizers for several years. I had union cards printed in every language and people from previously isolated groups began to sign.

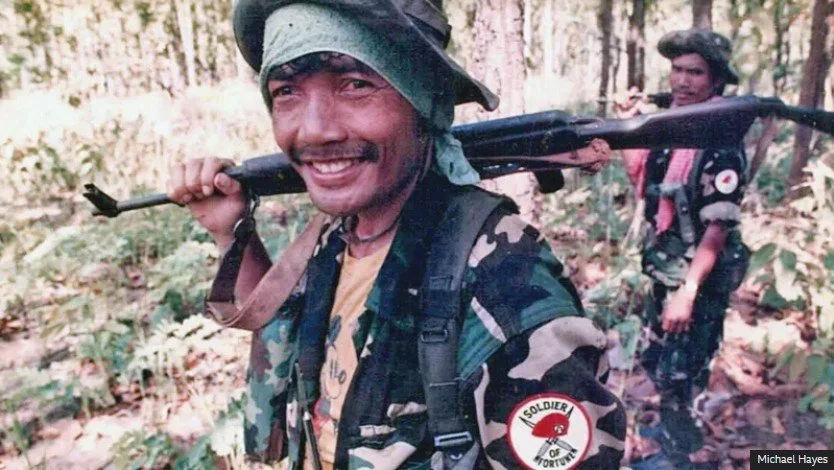

A very different looking Pastor Y Hin Nie during the Vietnam War.

The Montagnards were always friendly and took a leaflet but otherwise showed no interest in the union, either for or against. Having survived a life of combat and experiencing the slaughter of friends and loved ones, the last thing they wanted was involvement in further conflict. From their perspective, working at Kmart amounted to having won the lottery: earning far more money than they’d ever imagined and returning home to families safely waiting beneath a roof.

I discussed this dilemma with Kathleen and she introduced me to Pastor Y Hin Nie, who not only translated the Montagnard leaflets but was the global leader of their dispersed nation. (“Y” is the Montagnard equivalent of Mister, sometimes used as a prefix to full names.) We met in his home a week later and sitting across from him at the dining room table, learned of his unique background. Hin Nie had been raised in a monastery and educated by missionaries who taught him to be fluent in several languages and a devout Christian. He became a Colonel in the Montagnard resistance and accompanied them through the jungles of Vietnam to offer spiritual guidance but was always armed to fight when necessary. While seeking refuge in Cambodia to avoid pursuit by superior forces, he negotiated safe passage for his troops with the Khmer Rouge.

Hin Nie was a charming man who loved to talk about himself and sometimes feigned more knowledge about certain subjects than he really had. “One day, I gathered all the Montagnards together and converted them to Christianity,” he told me.

“Why did they all convert at once?” I inquired.

“Because I asked them to.”

I was curious to know what the indigenous religion had been like and posed the question. “They looked out at the jungle and saw how big it was,” he responded, spreading his arms for emphasis, “and so they worshipped it.”

I knew there must be more to deeply embedded spiritual beliefs that had endured for millennia, but turned the discussion to Kmart. The pastor informed me that he was very pro-union and validated my insights about the Montagnards’ lack of interest, but also shared that they frequently complained to him about management mistreatment.

“The company is taking advantage of their inability to communicate with the union,” I told him. “If I understood their issues, I’d be able do something about them. I would think that warrior spirits like your people would want to do more than just complain. They already know how to stand up for themselves but don’t understand how to do it in this society. How would you feel about holding a meeting with them, explain what the union is about and encourage them to join?”

Y Hin Nie readily agreed and two weeks later handed me seven translated union cards that his people had signed, explaining the rest wanted to discuss it with their wives. “Stay in contact with them,” he advised, “but don’t push people. Some will come around more quickly than others.”

The Kmart contract had good plant access language and I regularly toured the warehouse on all three shifts, accompanied by a local union officer. I began seeking out the Montagnards who always greeted me with a friendly disposition as I shook their hand. “Union! We fight for you,” I’d exclaim, holding up a card, hoping that the ones who didn’t fully understand my words would still feel the intensity behind them. At the very least, my presence in the middle of the night spoke volumes about my commitment. It was a long, slow process, but I always came away with a few new members.

Over time, I became increasingly intrigued by the Montagnards: short, slender people with affable personalities who’d fought in jungles for two decades but displayed no signs of the post traumatic stress that plagued so many American veterans. One would think they’d never thrown a punch in anger, let alone lived and died by the AK 47 for their entire adult lives. The only clue was rows of mysterious, ghoulish tattoos running up their arms from wrist to shoulder.

Hin Nie invited me back to his house and introduced me to a bilingual Montagnard employed at Kmart who worked on the Receiving docks and for the sake of convenience went by the name John. Other than the ubiquitous tattoos, he had the appearance and mannerisms of a polite but shy grocery clerk. John had in fact been a general in the Montagnard Resistance for over twenty years, leading hundreds of men into mortal combat against overwhelming odds.

He was willing to offer his broken English to serve as a liaison between me and his fellow expatriates and glad to participate in the membership drive. But he balked at my offer to become the Montagnard shop steward, saying he wasn’t qualified to represent people and didn’t want to become involved in disputes.

“You don’t have to take part in grievances if you’re not comfortable,” I told him. “Just let me know what their grievances are, and the steward from their department will handle the case. But I think it’s important for your people to see you as a leader in the union, just as you were a leader back home.”

The reluctant warrior finally agreed on that basis. I began receiving updates from John while visiting the Receiving Department and when necessary provided him with information or advice to take back to those with questions or issues. His involvement doubled the rate at which we signed cards. But it was incongruous to see this former war hero and leader of men reduced to unloading trucks, and yet delighted with his circumstances.

Montagnards File a Grievance

Significant changes in plant rules at Kmart warehouses were always made at a corporate level and then handed down to every plant manager with no regard for unique circumstance or union contracts. A year after I began organizing the Montagnards, the Employee Handbook was revised, requiring all forklift drivers to pass a test in English. Those who failed would be removed and assigned other work.

I found this extremely unreasonable as numerous Montagnards had been successfully driving lifts since the building opened without language presenting an obstacle. I filed a grievance on their behalf, requesting it immediately begin at my level, to which the company agreed.

Shortly thereafter, John had his first opportunity to sit at the bargaining table along with Executive Board members. Kmart had hired the Montagnards specifically because they didn’t speak English, but were now preparing to penalize them for it. Unfortunately, fair vs. unfair is not a legal argument and the contract was silent regarding literacy, so I was obliged to argue violation of seniority rights. I asked John to speak on behalf of his constituency about how this rule would affect their lives. When his remarks became halting and awkward, I interjected with questions to focus his attention. He was clearly far more intimidated by Kmart management than he had been by the Viet Cong.

Once we were finished, the plant manager candidly responded, “I hear what you’re saying but our hands are tied on this one. I discussed this with corporate and they have no flexibility.”

Upon receiving the written rejection I immediately filed for arbitration. Several weeks later I felt like fate had dealt me a good hand when the case was assigned to an adjudicator who’d recently given me a favorable decision. I began meeting with Hin Nie to explain the realities of arbitration and prep him to be my star witness.

The pastor frequently digressed from the case to discuss his own experiences in this country. The United States government considered him an important resource because he had connections in parts of the world that were beyond their diplomatic reach and treated him accordingly. He was periodically invited to Washington for meetings with members of Congress who skillfully pandered to his vanity and need to feel important.

“After my meeting with Senator Jesse Helms, I met with the Justice Department and explained the problems at Kmart. They assured me they would look into it!” Hin Nie proudly exclaimed as if I would consider this encouraging news. The agency actually has no jurisdiction over employment issues overseen by the Department of Labor and National Labor Relations Board.